The importance of net revenue retention (NRR) is well established. All other things equal, a higher NRR increases the size of your SaaS business, its growth rate, its profitability, and its valuation. And, importantly, it compounds year after year.

Over time, its impact on valuation is enormous—I have written about this for years. Most folks have gotten the memo by now.

But just as “growth at all costs” is unsustainable and inefficient, so is retention at all costs.

Benchmarking retention spend

A simple way to track and benchmark retention spending is: Annualized Cost to Retain Customers/ARR.

I like the numerator of this metric to be relatively broad and include all Customer Success, customer marketing, training, and customer support costs. Any cost incurrent to support and retain the customer, including the costs of the systems, should be included. Just keep it consistent from period to period. Some experts suggest excluding customer support costs because they are included in COGS, but to me, there is no reason they should not be included here. It’s not mutually exclusive, and they are an important part of customer satisfaction.

For the denominator, I prefer ARR instead of “revenue retained in the period” for two reasons. First, revenue up for renewal can change significantly from period to period, which adds noise to the metric. Second, using total ARR recognizes that all customers are continually being supported, and retention is not something that only happens at the time of renewal.

You can benchmark this metric if you want, but the reality is that some companies have an easier time retaining customers than others, and just because you may be spending more or less than average to retain customers does not mean you should necessarily increase or decrease your investment.

Let’s face facts:

Some customers will renew themselves year after year with little effort from you

Some customers will churn no matter what you do

Your product and use cases will make it easier or harder to retain customers than other SaaS companies

The ideal metric would measure the marginal cost of retention against the marginal improvement in retention. Of course, that’s hard to measure, but let’s explore.

How much should you spend to retain customers?

If a company invested one percent more of revenue in retaining customers, and that investment increased their retention rate by one percentage point, would that be a good trade-off or not?

Financially, a higher NRR will make the company grow faster and have a higher ARR over time, but the increased spending will lower profits (assuming the spending is maintained.) The higher revenue will make the company more valuable, and the higher growth rate and lower profitability will be captured in the Rule of 40, which will impact the company’s valuation multiple.

Said differently, higher NRR will increase ARR over time which will increase valuation, while the higher growth rate and higher expenses will create offsetting impacts on the valuation multiple, which may raise or lower the company’s valuation.

Using the most recent correlation between the Rule of 40 (which captures both growth and profitability), and SaaS valuation multiples, you can see that each percentage point improvement in the Rule of 40 increases the valuation multiple by about .06. (Slope of the line.)

Credit to Meritech Capital for this data.

That might not seem like a lot, but it ads-up and gets more significant over time as the growth rate naturally builds based on better retention.

With that relationship in mind, let’s look at two hypothetical SaaS companies to more clearly demonstrate the impact of retention spending on valuation. Company #1 is “Economy SaaS”; they spend 20% of revenue on retaining customers and have a 90% net renewal rate. Company #2 is “First Class SaaS,” They spend 25% of revenue retaining customers and have a 95% net renewal rate.

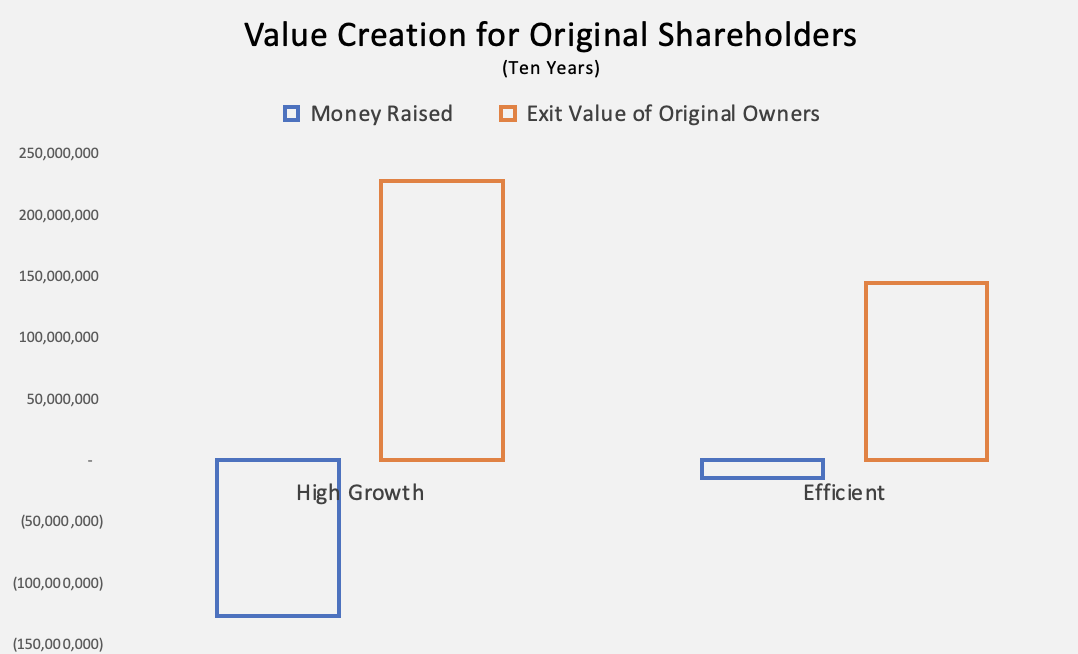

Holding all other things constant such as bookings and other expenses, First Class ends up with a higher Rule of 40 than Economy as their higher NRR improves growth which more than offsets the lower operating profit. With a higher Rule of 40, and thus a higher multiple, plus more ARR over time, First Class is more valuable than Economy, as shown in the chart below.

So we have always known that companies with higher retention are more valuable, but now we have a framework to account for the costs of retaining customers and its offsetting impact on valuation.

We asked earlier, “If a SaaS business spends one percent more of revenue to retain customers, and that results in a one percentage point improvement in NRR, is that good or bad? As the chart indicates, it’s a good thing. As you approach a two percent spend for every percentage point increase in NRR, however, the near-term valuation advantage disappears.

The valuation balancing act of retention spending

So what are the practical takeaways here?

For CEOs and CFOs, having the “1% for 1%” rule of thumb is helpful as you make investment decisions about how much to spend on customer retention. If you can spend one percent of revenue more on retention and increase the retention rate by one percent, do it.

And it works both ways. If you cut spending on retention from 25% of revenue to 20% of revenue, what will happen to retention? If NRR drops five percentage points, you have destroyed value; if it drops half that, you are in the grey zone in the near term but will be eroding value over time because of the cumulative loss of ARR.

In practice, it’s not easy to measure these things. There are long lags between changes in spending and changes in retention, and there is also monthly “noise” in the data. And as mentioned earlier, most retention and churn happen despite what you are doing, not because of it. So you can only make progress at the margin with CS spending.

That said, making investment decisions on customer retention in a complete vacuum is not helpful either. Hopefully, this analysis can help shape a framework that managers can use to make better, value-creating decisions.